Vol.6 Satoshi Saida

As long as I continue to be my toughest critic, I can continue to evolve as a player

Satoshi Saida

(Wheelchair tennis player)

At the fundamental level, sports provides an entertaining way for people to compete against each other in physical one-upmanship. But sports can also have a deeper impact, providing opportunities for personal growth and social transformation. Athletes have more than just fun on their minds as they entertain spectators with their physical feats; they also have broader goals and visions they hope to achieve through sports.

One athlete who embodies this characterization is veteran wheelchair tennis player Satoshi Saida, who continues to push himself in his training so that he never regrets his decision to take up the sport.

(Wheelchair tennis player)

At the fundamental level, sports provides an entertaining way for people to compete against each other in physical one-upmanship. But sports can also have a deeper impact, providing opportunities for personal growth and social transformation. Athletes have more than just fun on their minds as they entertain spectators with their physical feats; they also have broader goals and visions they hope to achieve through sports.

One athlete who embodies this characterization is veteran wheelchair tennis player Satoshi Saida, who continues to push himself in his training so that he never regrets his decision to take up the sport.

Still pushing himself at the age of 47

"I know that at my age, I need to take things a little slower", Saida says. "I just can't! (Laughs.) I keep training the way I used to when I was younger and end up overworking myself. It's in my nature to push myself to my limits. No matter how old I get or how physically challenging it gets for me, I want to always make sure I'm training until I can't move another muscle."

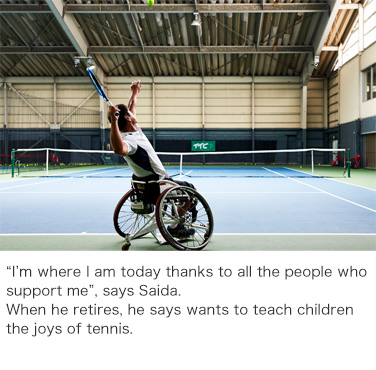

Saida's homecourt is located in Kashiwa, Japan. On this day, he is dripping with sweat as he plays against a younger coach. They play in an indoor court, which booms every few seconds with the sound of Saida's racket hitting the ball. It is hard to believe that this sound—as well as the powerful trajectory of the ball—are produced solely through upper-body strength. Saida also moves with surprising agility, rapidly moving right, left, forward, and back—and sometimes performing a quick turn. The former world champion has lost none of his enthusiasm for the sport. He trains at the court every day, after which he does weights and practices dashing.

"For twenty years now, I've spent four to six months of every year traveling overseas for matches", Saida says. "If you continue something for that long, things can start to feel repetitive. To help me focus, I try to stick to a fixed schedule. I go to bed early and wake up early, and then I have a good, solid breakfast. By paying the proper amount of attention to these basic things, I'm able to fully concentrate on the court. And nobody has to force me to do all this, because I genuinely love tennis. If you love something, you can go on even when things get tough."

Saida, who played baseball as a child, lost his left leg to bone cancer at the age of 12. "It was a living nightmare", he says. Noticing he had become despondent and was losing confidence, his parents introduced him to a local wheelchair basketball team.

"My teammates had all kinds of disabilities", he recalls. "Some had conditions that were even worse than mine. Learning about living with a disability from the older kids on the team made me feel more optimistic. They didn't let their conditions prevent them from living how they wanted and enjoying sports. I wanted to live just like them. Without that team, I wouldn't be where I am today. Later on, I took up tennis as well, and would have been happy to continue with basketball, but the team was discontinued. So, all that was left for me was tennis. (Laughs)."

"I know that at my age, I need to take things a little slower", Saida says. "I just can't! (Laughs.) I keep training the way I used to when I was younger and end up overworking myself. It's in my nature to push myself to my limits. No matter how old I get or how physically challenging it gets for me, I want to always make sure I'm training until I can't move another muscle."

Saida's homecourt is located in Kashiwa, Japan. On this day, he is dripping with sweat as he plays against a younger coach. They play in an indoor court, which booms every few seconds with the sound of Saida's racket hitting the ball. It is hard to believe that this sound—as well as the powerful trajectory of the ball—are produced solely through upper-body strength. Saida also moves with surprising agility, rapidly moving right, left, forward, and back—and sometimes performing a quick turn. The former world champion has lost none of his enthusiasm for the sport. He trains at the court every day, after which he does weights and practices dashing.

"For twenty years now, I've spent four to six months of every year traveling overseas for matches", Saida says. "If you continue something for that long, things can start to feel repetitive. To help me focus, I try to stick to a fixed schedule. I go to bed early and wake up early, and then I have a good, solid breakfast. By paying the proper amount of attention to these basic things, I'm able to fully concentrate on the court. And nobody has to force me to do all this, because I genuinely love tennis. If you love something, you can go on even when things get tough."

Saida, who played baseball as a child, lost his left leg to bone cancer at the age of 12. "It was a living nightmare", he says. Noticing he had become despondent and was losing confidence, his parents introduced him to a local wheelchair basketball team.

"My teammates had all kinds of disabilities", he recalls. "Some had conditions that were even worse than mine. Learning about living with a disability from the older kids on the team made me feel more optimistic. They didn't let their conditions prevent them from living how they wanted and enjoying sports. I wanted to live just like them. Without that team, I wouldn't be where I am today. Later on, I took up tennis as well, and would have been happy to continue with basketball, but the team was discontinued. So, all that was left for me was tennis. (Laughs)."

Saida's first big break came when he was 27. At the time, he had a steady job as a civil servant in his home prefecture of Mie. Although he had represented Japan in the Atlanta Olympics, he knew that if he wanted to be truly competitive on the world stage, he would need an environment more conducive to his training.

"It was around that time that I met someone from my current homecourt", he says. "There are very few places in Japan where you can practice wheelchair tennis and even fewer places where you can find training partners. But this person told me that at their court, I would be able to practice anytime I wanted and would also be given a job with a wheelchair manufacturer. Part of me wanted to give this a try, but another part of me was scared stiff. A lot of people around me said it was a bad idea, and I tend to play things safe by nature. I would have had to move and get a new job! I went back and forth on the offer for three years. What changed my mind was something that same person from the Kashiwa court told me: ‘You're good enough to compete against Americans and Europeans, and we're offering you an environment where you can properly train. This is your mantle to take on, and nobody else's'. If I didn't take on this challenge that nobody else was qualified for, I would have regretted it for the rest of my life. So I said, all right, let's do this."

In 2003, Saida became the first Japanese wheelchair tennis player to be honored as an International Tennis Federation World Champion. After receiving his award, Saida continued to train in earnest.

"Getting first place, winning a medal—these are all great and give you a sense of accomplishment", says Saida. "But in my case, instead of basking in the moment, I'm already looking ahead. For me, every day is a battle, and records are things of the past. It has been the same for the last twenty years. In that time, rackets and wheelchairs have evolved, and I've played a role in their development. The newer wheelchairs can provide the increased speed and stability, so that you can alter your playing style to take advantage of them. As long as I continue to be my toughest critic and never go easy on myself, I can continue to evolve as a player."

"It was around that time that I met someone from my current homecourt", he says. "There are very few places in Japan where you can practice wheelchair tennis and even fewer places where you can find training partners. But this person told me that at their court, I would be able to practice anytime I wanted and would also be given a job with a wheelchair manufacturer. Part of me wanted to give this a try, but another part of me was scared stiff. A lot of people around me said it was a bad idea, and I tend to play things safe by nature. I would have had to move and get a new job! I went back and forth on the offer for three years. What changed my mind was something that same person from the Kashiwa court told me: ‘You're good enough to compete against Americans and Europeans, and we're offering you an environment where you can properly train. This is your mantle to take on, and nobody else's'. If I didn't take on this challenge that nobody else was qualified for, I would have regretted it for the rest of my life. So I said, all right, let's do this."

In 2003, Saida became the first Japanese wheelchair tennis player to be honored as an International Tennis Federation World Champion. After receiving his award, Saida continued to train in earnest.

"Getting first place, winning a medal—these are all great and give you a sense of accomplishment", says Saida. "But in my case, instead of basking in the moment, I'm already looking ahead. For me, every day is a battle, and records are things of the past. It has been the same for the last twenty years. In that time, rackets and wheelchairs have evolved, and I've played a role in their development. The newer wheelchairs can provide the increased speed and stability, so that you can alter your playing style to take advantage of them. As long as I continue to be my toughest critic and never go easy on myself, I can continue to evolve as a player."

Seeking a life without regrets

Saida's current focus is on his potentially biggest stage yet—the Tokyo Paralympics. "Four years ago, I felt that my age was beginning to show", he says. "But how could I not want to compete in such a major event in my home country?"

Saida explains that part of his drive comes from wanting to give back to his supporters. "The world of wheelchair tennis is not big, but if you keep at it long enough, you gain a following", he says. "I think that's amazing. When I said I wanted to be the world's top player, a lot of people looked at me as if I was crazy. But once I'd said it, I needed to hold myself to my word. There was a time when I just wasn't performing well, but because I kept at it, people began to flock to me and support me. You don't convey anything by playing half-heartedly. It's only by being optimistic and working hard that you gain fans and supporters."

Saida knows that his career is nearing its end—but he already knows what he'll be doing in his next stage. "After retiring, I want to teach children the joys of tennis", he says. "After I lost my left leg, I became despondent, but discovering wheelchair tennis changed my life. I want to be someone who can empower others through sports—just as the older kids in my basketball team did for me. If you're optimistic and work hard, a path will open up for you. I want to be the person who can help open that path for others. After years of hesitating, I decided to become a pro, and I don't want to ever regret that decision. That means I have to continue challenging myself—something I'm doing right now, and something I will do for the rest of my life."

For Saida, the past twenty years represents a foundation from which he can continue to offer something to the world, beginning with the upcoming Tokyo Paralympics.

Saida explains that part of his drive comes from wanting to give back to his supporters. "The world of wheelchair tennis is not big, but if you keep at it long enough, you gain a following", he says. "I think that's amazing. When I said I wanted to be the world's top player, a lot of people looked at me as if I was crazy. But once I'd said it, I needed to hold myself to my word. There was a time when I just wasn't performing well, but because I kept at it, people began to flock to me and support me. You don't convey anything by playing half-heartedly. It's only by being optimistic and working hard that you gain fans and supporters."

Saida knows that his career is nearing its end—but he already knows what he'll be doing in his next stage. "After retiring, I want to teach children the joys of tennis", he says. "After I lost my left leg, I became despondent, but discovering wheelchair tennis changed my life. I want to be someone who can empower others through sports—just as the older kids in my basketball team did for me. If you're optimistic and work hard, a path will open up for you. I want to be the person who can help open that path for others. After years of hesitating, I decided to become a pro, and I don't want to ever regret that decision. That means I have to continue challenging myself—something I'm doing right now, and something I will do for the rest of my life."

For Saida, the past twenty years represents a foundation from which he can continue to offer something to the world, beginning with the upcoming Tokyo Paralympics.

Satoshi Saida

Saida was born in 1972 in Mie, Japan. He has used a wheelchair since the age of 12, when he lost his left leg to bone cancer. He has competed in six consecutive Paralympic Games, beginning with the 1996 Atlanta Games. Partnering with Shingo Kunieda for the Men's Doubles, he won gold at the 2004 Athens Paralympics and bronze at the 2008 Beijing and 2016 Rio Games. In 2003, Saida became the first Japanese wheelchair tennis player to be honored as an International Tennis Federation World Champion.

Words: Kosuke Kawakami Photography: Tsukuru Asada

── MUFG Bank supports the children of our future through the activities of Laureus. ──